US $460

| Condition | For parts or not working

:

An item that does not function as intended and is not fully operational. This includes items that are defective in ways that render them difficult to use, items that require service or repair, or items missing essential components. See the seller’s listing for full details.

|

| Seller Notes | “So-so condition, some homework pages ripped out, filled in, but includes the CD ROM.” |

Directions

Similar products from Other Equipment for Particular Medical Areas

Reusable mouthpieces for CONTEC Digital Spirometer CMS-SP10\SP10W,Pack of 50pcs

2005 Siemens Sonoline G20 Ultrasound System W/ C5-2 Convex Transducer & Printer

Philips Agilent HP Sonos 5500 Ultrasound W/ S4 / S12 / 11-3L Probe & Footswitch

DermaMed Solutions MegaPeel Platinum Series microdermabrasion system

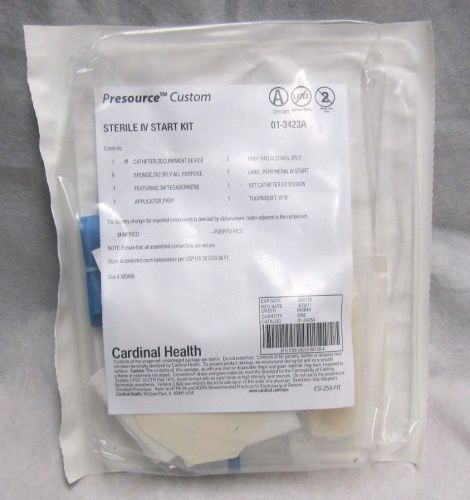

Cardinal Health Presource Custom Sterile IV Starter Kit 01-3423A Exp. : 03-2014

RN+Systems 30 Day Wheelchair Sensor #BPP-30WC Lot Of 5

Refurbished GE LOGIQ 9 W/ 7L Linear 10S Sector i12L Linear & 3.5C Convex Probes

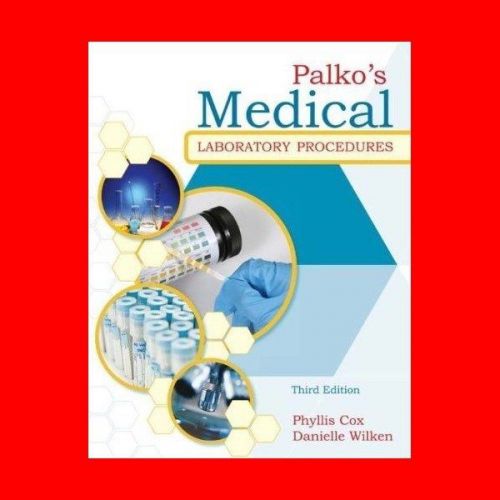

?BOOK:PALKO'S MEDICAL LABORATORY TESTING PROCEDURES 3RD ED,PATHOLOGY PRINCIPLES?

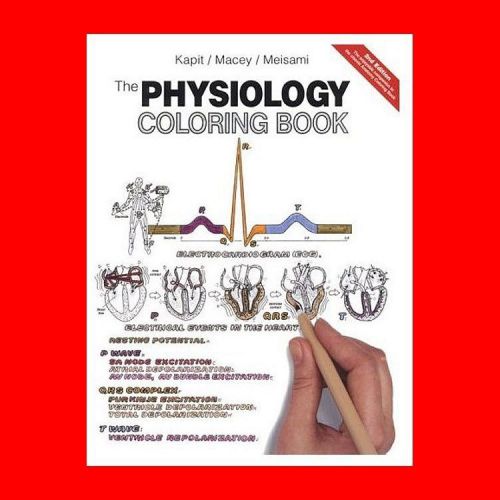

?THE PHYSIOLOGY COLORING BOOK:MEDICAL,OSTEOPATHY LEARN ANATOMY,ILLUSTRATED STUDY

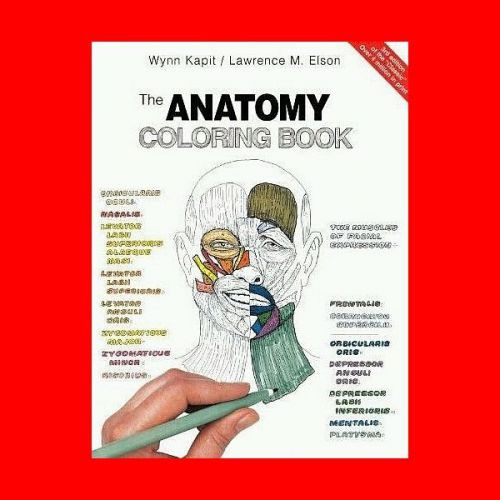

?THE ANATOMY COLORING BOOK:MEDICAL,OSTEOPATHY LEARN PHYSIOLOGY,ILLUSTRATED STUDY

STUDENT WORK BOOK:MEDICAL ASSISTING: ADMINISTRATIVE CLINICAL PROCEDURES:ANATOMY

Reusable mouthpieces for CONTEC Digital Spirometer CMS-SP10\SP10W,Pack of 100pcs

TBJ STAINLESS STEEL FORMALIN DISPENSER SINK HOOD ENCLOSURE CABINET WORKSTATION

Cooper Surgical Frigitronics Cryo-Plus Cervix Probe 2442, New

RCI Conchatherm III Servo Controlled Heater 380-80R

Cryomedics Cryosurgical System KR Med MT 600

Smith&nephew 7205322 Orbit Razorcut Blade 4.5mm ~ Lot of 4

GE 107365 Critikon 12FT Air Hose

GE 414873-001 Blood Pressure Tubing Dual Tube Submin Adult 3.6M

LeMaitre 4100-00 LeverEdge Contrast Injector ~ exp 2016/08

People who viewed this item also vieved

FDA CE Veterianry VET Ultrasound Scanner machine W Convex Probe high quality

FDA Veterianry Ultrasound Scanner machine Micro Convex Probe cardiac abdomen 3D

Veterinary Vet Ultrasound Scanner with Micro-Convex Probe external 3D software

Arthrex AR-1510FPR Femoral Right 7mm (Qty 1)

Byron Infusion Pump , Liposuction , Infiltration ,Tumescent, Lipo ,Wells Johnson

ARTHREX AR-1204AF-100 FLIPCUTTER II 10.0 MM IN DATE

Codman Surgical Spinal Orthopedic 90° Up 3mm Lumbar Kerrison Rongeur 53-1415

4 Assorted Size Medtronic Drill Bits

Covidien Appose ULC 35W Slim Body Skin Stapler (Lot of 12) 8886803712

Dynatron Dynatronics Ultrasound Muscle Stimulator Chiropractic Physical Therapy

TOUCH AMERICA Massage Table / Chair

Saunders 100399 Cervical HomeTrac Deluxe Neck Traction w/Case + Manual EXCELLENT

Broken Used Nebulizer Repairment

Lot 3: Lot of 20 Intermed, Drive, American Bantex Oxygen Regulator O2

Lot 2: Lot of 20 Intermed, Reliant, Inovo, American Med Oxygen Regulator O2

Chiropractic Physical Therapy IASTM Soft Tissue Guasha Crossfit Graston Massage

Chiropractic Adjustment Physical Therapy Treatment & Massage Table Power Hi-Lo

Quantum Cold Laser for Chiropractic. Low Level Laser Therapy Vityas LLLT

By clicking "Accept All Cookies", you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

Accept All Cookies